History of the Labor Movement

History of Labor Day

Labor Day: What it Means

Labor Day, the first Monday in September, is a creation of the labor movement and is dedicated to the social and economic achievements of American workers. It constitutes a yearly national tribute to the contributions workers have made to the strength, prosperity, and well-being of our country.

Labor Day Legislation

The first governmental recognition came through municipal ordinances passed in 1885 and 1886. From these, a movement developed to secure state legislation. The first state bill was introduced into the New York legislature, but the first to become law was passed by Oregon on February 21, 1887. During 1887 four more states — Colorado, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and New York — created the Labor Day holiday by legislative enactment. By the end of the decade Connecticut, Nebraska, and Pennsylvania had followed suit. By 1894, 23 more states had adopted the holiday, and on June 28, 1884, Congress passed an act making the first Monday in September of each year a legal holiday in the District of Columbia and the territories.

Founder of Labor Day

More than a century after the first Labor Day observance, there is still some doubt as to who first proposed the holiday for workers.

Some records show that Peter J. McGuire, general secretary of the Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners and a co-founder of the American Federation of Labor, was first in suggesting a day to honor those "who from rude nature have delved and carved all the grandeur we behold."

But Peter McGuire's place in Labor Day history has not gone unchallenged. Many believe that Matthew Maguire, a machinist, not Peter McGuire, founded the holiday. Recent research seems to support the contention that Matthew Maguire, later the secretary of Local 344 of the International Association of Machinists in Paterson, N.J., proposed the holiday in 1882 while serving as secretary of the Central Labor Union in New York. What is clear is that the Central Labor Union adopted a Labor Day proposal and appointed a committee to plan a demonstration and picnic.

The First Labor Day

The first Labor Day holiday was celebrated on Tuesday, September 5, 1882, in New York City, in accordance with the plans of the Central Labor Union. The Central Labor Union held its second Labor Day holiday just a year later, on September 5, 1883.

In 1884 the first Monday in September was selected as the holiday, as originally proposed, and the Central Labor Union urged similar organizations in other cities to follow the example of New York and celebrate a "workingmen's holiday" on that date. The idea spread with the growth of labor organizations, and in 1885 Labor Day was celebrated in many industrial centers of the country.

A Nationwide Holiday

The form that the observance and celebration of Labor Day should take was outlined in the first proposal of the holiday — a street parade to exhibit to the public "the strength and esprit de corps of the trade and labor organizations" of the community, followed by a festival for the recreation and amusement of the workers and their families. This became the pattern for the celebrations of Labor Day. Speeches by prominent men and women were introduced later, as more emphasis was placed upon the economic and civic significance of the holiday. Still later, by a resolution of the American Federation of Labor convention of 1909, the Sunday preceding Labor Day was adopted as Labor Sunday and dedicated to the spiritual and educational aspects of the labor movement.

The character of the Labor Day celebration has undergone a change in recent years, especially in large industrial centers where mass displays and huge parades have proved a problem. This change, however, is more a shift in emphasis and medium of expression. Labor Day addresses by leading union officials, industrialists, educators, clerics and government officials are given wide coverage in newspapers, radio, and television.

The vital force of labor added materially to the highest standard of living and the greatest production the world has ever known and has brought us closer to the realization of our traditional ideals of economic and political democracy. It is appropriate, therefore, that the nation pays tribute on Labor Day to the creator of so much of the nation's strength, freedom, and leadership — the American worker.

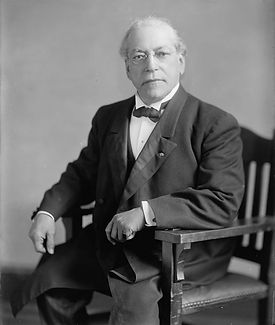

Samuel Gompers

The American labor leader Samuel Gompers (1850-1924) was the most significant single

figure in the history of the American labor movement. He founded and was the first president of the American Federation of Labor.

Few great social movements have been so influenced by one man as was the American labor movement by Samuel Gompers. He virtually stamped his personality and viewpoint on the American Federation of Labor (AFL). This heritage included both Gompers's social conservatism and his truculent firmness on behalf of the organized skilled workers of the country. His is a unique success story, of an utterly penniless immigrant who became the confidant of presidents and industrialists.

Gompers was born on Jan. 27, 1850, in east London, England. His family was Dutch-Jewish in origin and had lived in England for only a few years. The family was extremely poor, but at the age of 6 Gompers was sent to a Jewish free school, where he received the rudiments of an education virtually unknown to his class. The education was brief, however, and Gompers was apprenticed first to a shoemaker and then in his father's cigar-making trade. In 1863, when Gompers was 13, the family moved to the tenement slums of the Lower East Side of New York City. The family soon numbered 11 members, and Gompers again went to work as a cigar-maker.

Cigar-Makers Union

Naturally gregarious and energetic, Gompers joined numerous organizations in the bustling immigrant world of New York City. But from the start nothing was so important to him as the small Cigar-makers' Local Union No. 15, which he joined with his father in 1864. Gompers immediately rose to leadership of the group. At the age of 16 he regularly represented his fellow workers in altercations with their employers, and he discussed politics and economics with articulate workingmen many years his senior.

This was a time of technological flux in cigar-making, as in practically every branch of American industry. Machines were being introduced which eliminated many highly skilled workers. The cigar-makers were distinguished, however, by the intelligence with which they studied their problems. The nature of the work—the quietness of the process, for example—permitted and even encouraged discussion of economic questions, and this environment provided Gompers with an excellent social schooling. The most significant influence upon his life was a formerly prominent Scandinavian socialist, Ferdinand Laurrel, who had become disillusioned with Marxism and taught Gompers that workingmen ought to avoid both politics and utopian dreaming in favor of winning immediate "bread and butter" gains in their wages, hours, and conditions.

In fact, Gompers had many contacts with socialists, though, from his earliest days, he had little time for their ideals. Basing his own unionism on a "pure and simple" materialistic approach, he built the Cigar-makers' International Union into a viable trade association despite technology and unsuccessful strikes.

American Federation of Labor

With Adolph Strasser, the head of the German-speaking branch of the Cigar-makers' Union (Gompers led the English-speaking branch), and several other trade union leaders, Gompers helped to set up in 1881 a loose federation of trade unions which, in 1886, became the AFL. Founded during the heyday of the Knights of Labor, the AFL differed from the older organization in nearly every respect. The Knights emphasized the solidarity of labor regardless of craft and admitted unskilled as well as skilled workers to membership. The AFL, with Gompers as its president, was a federation of autonomous craft unions which admitted only members of specific crafts (carpenters, cigar-makers, and so on) and made no provision for the unskilled. The Knights looked forward to a society in which the wage system would be abolished and cooperation would govern the economy, whereas the AFL unions were interested only in improving the day-to-day material life of their members.

The socialists' attempt to capture the AFL in 1894 did succeed in unseating Gompers for a year, but he was firmly back in power by 1895 and, if anything, more bitterly hostile to socialism in the unions than ever.

"Socialism holds nothing but unhappiness for the human race," Gompers said in 1918. "Socialism is the fad of fanatics … and it has no place in the hearts of those who would secure the fight for freedom and preserve democracy." Throughout his career he inveighed against the flourishing Socialist party and the numerous attempts to form revolutionary unions. Although many forces account for the failure of socialist thought among American unions, Gompers's influence at the head of the movement for 40 years cannot be discounted.

Devotion to Unionism

However, if Gompers was hostile to the socialists, he was as devoted to the cause of unionism as any other American labor leader before or since. He was the first national union leader to recognize and encourage the strike as labor's most effective weapon. Further, when issued an injunction in 1906 not to boycott the antilabor Buck Stove and Range Company, he defied the courts (albeit gingerly) and was sentenced to a year in prison for contempt (a conviction later reversed on appeal). Gompers spent only one night in jail (a rare distinction among labor leaders of his day) and, characteristically, was contemptuous of, rather than sympathetic with, those with whom he shared his cell. But his devotion to unionism and the rhetoric with which he denounced avaricious industrialists matched anything of his time.

National Prominence

Although the leader of a socially disreputable movement, Gompers had good relations with several presidents and became something of an adviser to president Woodrow Wilson. In 1901 he was one of the founders of the National Civic Federation (an alliance of businessmen willing to tolerate unions and conservative union leaders), and Wilson found it politically expedient and worthwhile to have the support of the AFL during World War I. Gompers supported the war vigorously, attempting to halt AFL strikes for the duration and denouncing socialists and pacifists. He served as president of the International Commission on Labor Legislation at the Versailles Peace Conference and on various other advisory committees.

During the 1920s, though in failing health, Gompers served as a spokesman for the Mexican revolutionary government in Washington and considered himself instrumental in securing American recognition of the new regime. He was received with high honors by President Plutarco Elias Calles in 1924, but, realizing that the end was near, Gompers returned early to the United States and died in San Antonio, Tex., on December 13. Characteristically, his last words were: "Nurse, this is the end. God bless our American institutions. May they grow better day by day." What had begun as expedient for Gompers—acceptance of the capitalist system and working within it—had become his gospel. Indeed, he was one of the makers of the modern institutions of which he spoke in that he won for capitalism the loyalty of labor and for labor a part in industrial decision making.

Gompers the Man

Among friends, Gompers was gregarious and convivial. He enjoyed eating and drinking, sometimes excessively (he was a vociferous enemy of prohibition), and at home he was the classic 19th-century paterfamilias with a retiring, worshipful wife and a large brood of deferential children.

Gompers first made his reputation as an orator and always delivered a speech well. He spoke widely in the cause of the AFL, rose to great heights of eloquence on occasion, and thanks to an agile mind and sharp tongue was rarely bested in debate. He mixed with equal ease among awkward workmen and in the polished society of Washington's highest circles. He had been a militant anticlerical in his youth and never attended a church or synagogue except to speak on labor's behalf. Although of Jewish heritage and education, he did not think of himself as a Jew or, for that matter, as a member of any religion. None of his books was distinguished except his autobiography, Seventy Years of Life and Labor (1925).

Further Reading

Gompers's autobiography, Seventy Years of Life and Labor (2 vols., 1925; rev. ed. in 1 vol., 1943), is indispensable. The most comprehensive and authoritative biography is Bernard Mandel, Samuel Gompers (1963). Also valuable are Philip Taft, The A. F. of L. in the Time of Gompers (1957), and Marc Karson, American Labor Unions and Politics, 1900-1918 (1958). The best among the brief surveys of American labor are Foster Rhea Dulles, Labor in America (1949; 3d ed. 1966); Henry Pelling, American Labor (1960); and Thomas R. Brooks, Toil and Trouble: A History of American Labor (1964).

Article taken from here.